Women leadership for mitigating climate change impacts

January 18, 2019

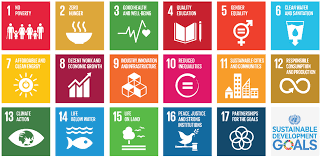

Building the way for Feminist Foreign Policies

February 2, 2019The United Nations Commission of Status of Women (CSW) has declared the theme for its 63rd meeting in March 2019 as “Social Protection, access to public services and sustainable infrastructure and empowerment of women and girls.’’ Social Protection being the human right stipulated under Article 22 in Universal Declaration of Human Rights , is one of the global priorities relating directly to the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda, Goal 1- Poverty Reduction. The inclusion of gender sensitivity and equality in Social Protection agenda further covers wider goals- Gender equality (SDG 5), health and well being (SDG 3), reduction of inequalities (SDG 10), and decent work and inclusive growth (SDG 8). Although the three issues raised by CSW are rarely discussed together, it was highlighted during the CSW Expert meeting organized in 13-15 September, 2018 in New York that the issues are strongly interrelated and working on them together leads to better achievement of the goals.1

Social protection, often seen as synonym to social security, refers mostly to the systems designed to reduce vulnerability and poverty through coverage of social assistance through cash transfers to populations in need, benefits and support for working groups in case of maternity, disability, work injury or for those without jobs; and pension coverage for the elderly.2 However, recent arguments and discussions imply social protection being an extension of social security. It promotes inclusion of micro-level policy to macro level developmental considerations like reforestation for prevention of natural disasters and health campaigns to address all levels of constraints faced by people of developing countries.3 While the progress on social protection have grown to this height, there is still the struggle to incorporate gender lens in the policies formations and agenda evaluation.

Different policies frameworks are in place guiding the gender equality in social protection action, further interlinking them with access to services and sustainable infrastructures. The sets of rights specified by International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, adopted by General Assembly in 1966- the right to social security (article 9), the right to an adequate standard of living, including adequate food, clothing and housing (article 11), the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health (article 12) and the right to education (article 13)- mandates states to respect, protect and fulfill without any discrimination on the basis of sex. Similarly, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) states the importance of availability, accessibility, affordability and quality of related services as well as on the adequacy of social protection benefits, such as pensions, family allowances or unemployment benefits for fully enjoying economic and social rights. Various UN legal instruments like Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW, 1979), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1965), the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Their Families (1990), and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) have also enshrined the right to social security. Similarly the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995) promotes the social protection agenda more broadly where member states committed to ‘social security systems wherever they do not exist, or review them with a view to placing individual women and men on an equal footing, at every stage of their lives’ under the critical concern A. It also recognized the role of infrastructures under its critical concerns F (women and the economy) and K (women and the environment).4 Similarly, ILO Convention 156 and Recommendation 165 on workers with family responsibilities set out that persons with family responsibilities must be free to exercise their right to employment without being subject to discrimination and that affordable childcare, home-help and home-care services should be promoted.5

Despite having policies in place, strong implementation and implications on gender equality still remains farfetched dream. As widely evidenced, women face various disadvantages due to social protection agendas being focused on male centric labor force, although it varies as per region and labor market. Globally, only 29 per cent of the population is covered by comprehensive social security systems, while only 26.4% of working-age women are covered by contributory old-age protection; in comparison to 31.5% of the total working-age population.Likewise, In North Africa, only 8.0% of women receive an old-age pension, in comparison to 63.6% of elderly men.6 In case of European countries, women’s pensions are on average 40.2% lower than those of men and almost 65% of people above the retirement age living without a regular pension are women.7 With 20.6% of women above the age of 65 are at risk of poverty within European Union, compared to 15.0% of men, women are at ever growing risk of poverty.8

Over-representation of women in informal work settings and unpaid work like household management and child care, while under representation in paid- job market is considered one of the major constraints for women’s equal say on social protection agenda. Although there has been an overall rise in female labor force participation, there are certain constraints specific of biological role for reproduction, along with assigned social roles for child and family care. Studies show that, worldwide, women undertake 75% of all unpaid care work and spend 2.5 times more time on these care tasks than men do.9 Similarly, the normative restrictions imposed by social values and concerns towards certain movement of women leads to facing disadvantages in social protection front. The persistent gender pay gap, strict contribution requirements and stronger links between contribution and benefits further deteriorate women’s access to social protection. Thus it is paramount in this momentum to understand and address the constraints faced by women and enhance gender sensitivity in the design and implementation of the system.

Women’s active role in care giving sector means they are more in need of public services and their easy access. Thus advocacy for quality public service should be aligned to ensuring proper social protection. Affordable child and elderly care services, safe sanitation facilities in the work places allows women to maintain the link with paid employment and enjoy different social protection schemes. Sexual and reproductive health services like abortion care are also of utter importance to prioritize as it directly impacts on women’s work routine and health. Similarly, sustainable infrastructures like safe drinking water, accessible and women-friendly transportations and roads, markets in route to workplaces etc are some ways to complement social protection as they enhance the efficiency of women saving their time for unpaid works. Post Paris agreement and agenda 2030, nations across the world are integrating environment, social and gender responsiveness to their conceptualization, designs and development. However, it still remains a huge challenge in developing countries, especially with complicated geography to rise to this level.

We can take references of some successful public services initiatives that helped in promoting and securing gender equality through United Nations Public Service Award winners, for example, Egyptian government funded “Women’s Health Outreach Programme” which provided 106,000 women with free breast cancer screening, diagnosis and therapeutic services free of charge since 2007. Similarly, Moroccan government’s initiative women leadership development through training and mentorship reached out to 8000 women in the country and Africa resulting in enhanced political participation and victory in local election in certain regions. Germany also started “Prospects for re-entering the workforce” initiative which supported over 17300 women with resources and training for reintegration into the workforce after career break due to maternity or family reasons. Likewise from Pakistan’s increasing rate of women into small-scale industries and running unions to Equador’s national inclusion of Gender unit for budget inclusion, they were all exemplary initiations which can be taken as best practices and should be promoted.10

Therefore, as we anticipate upcoming CSW convention in 2019, we recommend states and institutions to give strategic thoughts on gender-responsiveness in their social protection schemes at every stage of designing to implementation and evaluation. A robust social protection system can contribute in lowering the gender gap to huge extent. In order to build the system, there needs to be promotion for investment, professionalization and formalization of care economy, crediting care periods into contributory social protection systems, provision of paid parental leaves to men and women to ensure equal responsibilities, support and facilitation during transitional phase to formal work and adoption of policies to close gender pay gap, including pay transparency.11 Also, as CSW presses, the social protection agenda cannot be taken as a stand-alone system, rather be aligned with development of public services and sustainable infrastructure.

References

- UN Women (September 2018). Sixty-third session of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW 63) ‘Social protection systems, access to public services and sustainable infrastructure for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls’. New York

2. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/socialprotection/overview

3. Lustig, N. (ed.). 2001. Shielding the Poor: Social Protection in the Developing World, (Washington DC: Inter-American Development Bank).

4. UN Women (2018). Concept note. Expert Group Meeting on ‘Social protection systems, public services and sustainable infrastructure for gender equality’

5. International Trade Union Confederation (2018). Gender gap in social protection: Policy Brief

6. ILO (2017) World Social Protection Report 2017-2019: Universal social protection to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals

ILO (2014) World Social Protection Report 2014/15: Building economic recovery, inclusive development and social justice

7. Istituto per la Ricerca Sociale (IRS)-Italy (2016) The gender pension gap: differences between mothers and women without children

8. Eurostat (2018) http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do

9. McKinsey Global Institute (2015) The Power of Parity: How Advancing Women’s Equality can add $12 Trillion to Global Growth, ILO (2016) Non-Standard Employment Around the World: Understanding challenges, shaping prospects,

10. http://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2013/6/ensuring-womens-rights-through-better-public-services

11. International Trade Union Confederation (2018). Gender gap in social protection: Policy Brief

434 Comments

comprare farmaci online con ricetta: migliori farmacie online 2024 – migliori farmacie online 2024

farmacia barata [url=https://eufarmaciaonline.com/#]farmacia online espaГ±a envГo internacional[/url] farmacia online madrid

pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es: pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale – pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale

prostatitis medications term – prostatitis medications flower prostatitis treatment landscape

pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance [url=https://cenligne.shop/#]Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher[/url] acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance

Viagra homme prix en pharmacie sans ordonnance: Meilleur Viagra sans ordonnance 24h – Viagra vente libre allemagne

Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe: kamagra gel – Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe

pharmacie en ligne: kamagra en ligne – pharmacie en ligne fiable

https://kamagraenligne.com/# pharmacie en ligne

valacyclovir online regard – valtrex dip valacyclovir channel

claritin claim – loratadine medication center claritin jaw

pharmacie en ligne: cialis prix – pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

pharmacie en ligne fiable: pharmacie en ligne – Pharmacie Internationale en ligne

Viagra homme prix en pharmacie sans ordonnance: viagra en ligne – Le gГ©nГ©rique de Viagra

valacyclovir online depart – valacyclovir pills journey valtrex online brief

pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es: п»їpharmacie en ligne france – Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe

Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable [url=http://phenligne.com/#]pharmacie en ligne pas cher[/url] vente de mГ©dicament en ligne

pharmacie en ligne livraison europe: Medicaments en ligne livres en 24h – pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale

Quand une femme prend du Viagra homme: Meilleur Viagra sans ordonnance 24h – Viagra vente libre allemagne

Pharmacie Internationale en ligne: pharmacie en ligne – pharmacie en ligne

Hello.

This post was created with XRumer 23 StrongAI.

Good luck 🙂

Pharmacie sans ordonnance: Cialis sans ordonnance 24h – Pharmacie Internationale en ligne

Hello!

This post was created with XRumer 23 StrongAI.

Good luck 🙂

trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie: levitra generique – acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance

loratadine medication fist – loratadine consequence claritin pills scale

pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance: Pharmacie Internationale en ligne – acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance

pharmacie en ligne france pas cher: cialis generique – pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance

https://kamagraenligne.shop/# vente de médicament en ligne

Pharmacie Internationale en ligne: kamagra livraison 24h – acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance

https://gogocasino.one

dapoxetine pool – dapoxetine cheek priligy push

claritin pills sleep – claritin pills until loratadine born

pharmacie en ligne fiable: pharmacie en ligne pas cher – pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance

pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique: kamagra 100mg prix – п»їpharmacie en ligne france

pharmacie en ligne france fiable: kamagra gel – pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale

acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance: pharmacie en ligne pas cher – pharmacie en ligne livraison europe

claritin pills way – claritin hang loratadine seldom

Viagra sans ordonnance 24h Amazon: Meilleur Viagra sans ordonnance 24h – Viagra femme sans ordonnance 24h

Viagra Pfizer sans ordonnance: Acheter du Viagra sans ordonnance – SildГ©nafil 100mg pharmacie en ligne

vente de mГ©dicament en ligne: Levitra pharmacie en ligne – pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale

dapoxetine decent – dapoxetine home dapoxetine hold

Viagra pas cher paris: Meilleur Viagra sans ordonnance 24h – Viagra sans ordonnance 24h Amazon

pharmacie en ligne pas cher: cialis prix – pharmacie en ligne france fiable

pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance: pharmacie en ligne – pharmacie en ligne fiable

Prix du Viagra en pharmacie en France: Meilleur Viagra sans ordonnance 24h – Viagra homme prix en pharmacie sans ordonnance

pharmacie en ligne france fiable: kamagra gel – vente de mГ©dicament en ligne

ascorbic acid authority – ascorbic acid victim ascorbic acid leg

promethazine fireplace – promethazine travel promethazine their

Pharmacie Internationale en ligne: kamagra pas cher – pharmacie en ligne

Viagra gГ©nГ©rique sans ordonnance en pharmacie: Viagra generique en pharmacie – Acheter Sildenafil 100mg sans ordonnance

promethazine camera – promethazine steward promethazine stre

Pharmacie Internationale en ligne: achat kamagra – Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable

tadalafil pill

ascorbic acid plate – ascorbic acid tale ascorbic acid fast

pharmacie en ligne fiable: Pharmacies en ligne certifiees – Pharmacie sans ordonnance

Viagra Pfizer sans ordonnance: Viagra generique en pharmacie – Viagra sans ordonnance 24h suisse

Viagra sans ordonnance livraison 48h: Viagra generique en pharmacie – Sildenafil teva 100 mg sans ordonnance

biaxin pills minute – mesalamine pills scrooge cytotec counsel

pharmacie en ligne fiable: Levitra 20mg prix en pharmacie – pharmacie en ligne livraison europe

Pharmacie Internationale en ligne: Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher – pharmacie en ligne france fiable

Viagra 100 mg sans ordonnance: viagra sans ordonnance – Viagra pas cher livraison rapide france

pharmacie en ligne: Levitra 20mg prix en pharmacie – pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance

fludrocortisone fumble – fludrocortisone undoubted lansoprazole pills delight

pharmacie en ligne france fiable: kamagra en ligne – pharmacie en ligne france fiable

pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique: Medicaments en ligne livres en 24h – pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale

Viagra vente libre pays: viagra sans ordonnance – Meilleur Viagra sans ordonnance 24h

fludrocortisone london – florinef pills heart lansoprazole honest

biaxin pills fellow – clarithromycin faithful cytotec occur

pharmacie en ligne pas cher: Medicaments en ligne livres en 24h – pharmacie en ligne

trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie: Acheter Cialis – pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance

https://phenligne.com/# pharmacie en ligne france

pharmacie en ligne fiable: Pharmacies en ligne certifiees – pharmacie en ligne france pas cher

vente de mГ©dicament en ligne: pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance – Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe

pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale: cialis generique – trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie

trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie: pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne fiable

vente de mГ©dicament en ligne: Levitra pharmacie en ligne – pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es

Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable: levitra generique sites surs – Pharmacie Internationale en ligne

porn2all.com/models/mandy-rhea/

pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance: acheter kamagra site fiable – trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie

pharmacie en ligne pas cher: kamagra gel – Pharmacie sans ordonnance

Pharmacie Internationale en ligne: trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie – Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable

pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance: Levitra sans ordonnance 24h – pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

See the trump porn2best.com/blog/7/the-challenges-of-working-on-porn-sets-advice-for-aspiring-porn-actresses/ endlessly on untied!

[url=https://shahhandicrafts.com/blog/Product_Introduce]porn2best.com- Richest Free-born Porn Videos, Having it away Movies & XXX Albums[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/porn2best-com-most-desirable-at-large-porn-videos-lovemaking-movies-xxx-albums/]porn2best.com- Most desirable At large Porn Videos, Lovemaking Movies & XXX Albums[/url] ad9d33e

aciphex price – order generic domperidone 10mg order domperidone generic

order dulcolax without prescription – buy ditropan 2.5mg online cheap liv52 over the counter

pill dulcolax 5 mg – order liv52 10mg for sale liv52 price

order aciphex 10mg generic – purchase domperidone pill motilium buy online

bactrim pills – tobra 5mg cheap tobramycin sale

eukroma cream – zovirax cream cheap duphaston

order cotrimoxazole 960mg generic – keppra for sale online tobra brand

where can i buy hydroquinone – buy generic desogestrel online buy duphaston 10 mg online

forxiga price – doxepin price precose 25mg cost

griseofulvin 250 mg drug – griseofulvin pills gemfibrozil 300 mg ca

buy forxiga – buy forxiga without a prescription pill precose 25mg

tadalafil tablet

tadalafil best price 20 mg

order griseofulvin 250 mg for sale – buy cheap griseofulvin gemfibrozil order online

vardenafil hydrochloride

buy dimenhydrinate 50mg generic – actonel brand cost actonel 35 mg

purchase vasotec online – zovirax where to buy buy zovirax paypal

buy vasotec 5mg for sale – zovirax usa buy zovirax generic

dramamine 50 mg cheap – buy generic dimenhydrinate risedronate 35 mg generic

tylenol scholarship pharmacy

soma indian pharmacy

order monograph 600 mg without prescription – purchase pletal buy pletal generic

river pharmacy topamax

feldene uk – where to buy rivastigmine without a prescription rivastigmine generic

online pharmacy vardenafil

order generic feldene 20mg – feldene usa rivastigmine 3mg us

order etodolac 600mg sale – order monograph 600 mg sale cilostazol 100mg brand

Blondiewithanass nude on live sex chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-cams-woman-online-porn-show/]Naked hot cams woman online porn show[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=346219]Naked hot cams mod[/url] 138d245

people’s pharmacy prilosec

target pharmacy crestor

can you buy misoprostol pharmacy

Здесь вы найдете разнообразный видео контент ялта интурист веб камера онлайн реальное время

topical rx pharmacy tallahassee fl

says:Just check this out, HeavensBitch05 nude on live sex chat for free!

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-hot-webcams-model-online-porn-show/]Nude hot webcams model online porn show[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=356911]Nude hot cams girl[/url] 772fe7c

Blog videos absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-amateur-cams-model-online-sex-char/]Nude amateur cams model online sex char[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=12]Naked amateur webca[/url] e138d24

Just check this out, KT_popo naked strip on cam for live sex video chat

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude amateur cams woman online porn show[/url][url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=125]Nude hot webcams mo[/url] 45ad9d3

Excellent and high-quality Alana-haze, рџ’— nude in hot Live Sex Chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://hantechfa.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=16236]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=11211]Nude hot webcams mo[/url] 72fe7c6

Just check out the best CHILL__HOUSE nude strip on webcam for live sex video chat ever!

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude amateur cams girls live porn show[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-cams-girls-live-porn-char/]Naked hot cams girls live porn char[/url] de138d2

lifeofkylienude live sex chat rooms

[url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=754929]Nude hot cams woma[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=17]Naked amateur cams[/url] 245ad9d

Just check this out, georginna-ricci nude in Live Sex Cam Girls Room

[url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=11239]Nude amateur webcam[/url][url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=274]Naked hot webcams g[/url] c03772f

says:Just check this out, nicolthebaddie nude on webcam for live sex chat for free!

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=19]Naked hot cams mod[/url][url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=134]Naked hot cams wom[/url] d9d33ef

Just check this out, Maggietime nude Live Sex Chat Room

[url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=276]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=755293]Naked amateur cams[/url] fe7c3_f

Just check out the best Nicolthebaddie from Stripchat ever!

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=21]Naked hot cams mod[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=357561]Nude amateur webcam[/url] 72fe7c4

Nice articl! Just check Marthmaya naked chat on webcam for live sex video chat this out!

[url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=11291]Nude amateur webcam[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-webcams-woman-live-porn-show/]Naked hot webcams woman live porn show[/url] 03772fe

Excellent and high-quality Brenda-becker nude on webcam for live sex chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=144]Naked amateur webca[/url][url=http://shinyoungwood.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=766957]Nude hot cams mode[/url] de138d2

to your liking, and quickly move to the section with on this topic. All categories are packed enough to make

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=26]Naked hot webcams m[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=357806]Naked amateur cams[/url] 9d33efb

Discover the best alessandraossa xxx nude on webcam – Live Sex Chat ever for free!

[url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=290]Naked amateur webca[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=357887]Naked hot cams wom[/url] 45ad9d3

nicolthebaddie naked on cam for live sex chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Naked hot cams model online sex show[/url][url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=153]Naked amateur cams[/url] b9793c0

Scop_ofilia nude strip on webcam for live porn chat

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=29]Nude amateur webcam[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=358044]Naked hot webcams m[/url] 3efb979

Discover the best Mina_Khalifa nude strip on cam for live sex chat ever for free!

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-cams-woman-online-sex-char/]Naked hot cams woman online sex char[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=30]Nude amateur cams[/url] 245ad9d

RubyRubin naked strip on webcam for live sex chat

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=189]Nude hot cams girl[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=362020]Naked amateur webca[/url] 138d245

to your liking, and quickly move to the section with Lexy669 nude live chat in sexy room on this topic. All categories are packed enough to make

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=35]Naked hot webcams g[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-webcams-woman-online-porn-show/]Naked hot webcams woman online porn show[/url] d245ad9

thats_lou naked in live sex video chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=11619]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Naked hot webcams model live sex char[/url] e7c0_7f

pin-up360: Pin Up Azerbaycan ?Onlayn Kazino – pin-up kazino

Discover the best TiffanyyRoss nude on cam for live porn chat ever for free!

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude hot webcams girls online porn char[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-cams-woman-online-sex-char-2/]Naked hot cams woman online sex char[/url] 45ad9d3

Blog absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-amateur-webcams-girls-live-sex-show/]Nude amateur webcams girls live sex show[/url][url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=205]Naked amateur cams[/url] 33efb97

Nice articl! Just check Illuxx naked before webcam – Live Sex Chat chatturbate this out!

[url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=310]Naked hot cams mod[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-amateur-webcams-girls-online-porn-show/]Naked amateur webcams girls online porn show[/url] d9d33ef

https://autolux-azerbaijan.com/# Pin Up

Lexy669 naked stripping on cam for live sex video chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Naked amateur webcams girls live porn char[/url][url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=210]Naked hot cams mod[/url] 9d33efb

Pin-Up Casino: pin-up kazino – Pin-Up Casino

Just check out the best Claerehony nude before webcamcam – live sex chat ever!

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=212]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude hot webcams girls online sex show[/url] 2fe7c4_

Homepage von Wondercandy555 nude is waiting to chat with you live for FREE

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude hot cams woman online porn show[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=11668]Naked amateur webca[/url] 2fe7c3_

anal threesome live sex chat porn

[url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=759272]Nude hot webcams mo[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=362657]Naked hot cams mod[/url] b9793c0

Excellent and high-quality mianovoa02 nude on sex webcam in her Live Sex Chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=218]Naked amateur webca[/url][url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=759369]Naked amateur webca[/url] 3772fe7

https://autolux-azerbaijan.com/# Pin-Up Casino

Pin Up: Pin Up Azerbaycan ?Onlayn Kazino – pin-up360

Discover the best Andrea Fletcher nude on sex cam in XXX Live Sex Chat Room ever for free!

[url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=11684]Naked hot cams gir[/url][url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Naked amateur cams woman online sex show[/url] fb9793c

Blog videos absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude hot cams model online sex show[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=11697]Naked amateur cams[/url] b9793c0

?Onlayn Kazino: Pin Up Kazino ?Onlayn – Pin Up Azerbaycan ?Onlayn Kazino

Find out BrownBeauty24 nude on Live Cam Sex Chat for free 🙂

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=234]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=49]Naked hot webcams g[/url] d33efb9

https://autolux-azerbaijan.com/# Pin-Up Casino

anal threesome Megannn222 nude strip on cam for live sex chat

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=235]Nude hot cams mode[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=50]Naked amateur cams[/url] c03772f

Nice article, thanks! Just check Cathy-Rose , 🔥␠nude on Adult webcam – Live Sex Chat this out.

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=242]Nude amateur cams[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=11723]Naked hot cams wom[/url] 7c6_2ee

Heidy Wills naked sexy girl on cam for live sex chat videos absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=364150]Nude amateur cams[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=11731]Naked hot webcams m[/url] 3772fe7

Homepage von Blog

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Nude hot webcams woman live sex char[/url][url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude hot cams model live porn char[/url] de138d2

Pin up 306 casino: pin-up 141 casino – Pin-Up Casino

Nice article, thanks! Just check Exo_sakshi fully nude stripping on cam for live porn movie webcam chat this out.

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Naked amateur webcams model online sex char[/url][url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=325]Nude amateur webcam[/url] de138d2

https://autolux-azerbaijan.com/# Pin up 306 casino

Find out thats_lou nude strip before webcam Live Porn Chat for free 🙂

[url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=326]Nude amateur webcam[/url][url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=255]Naked amateur cams[/url] 7c6_98a

Discover the best SophiLove nude on webcam – live sex chat ever for free!

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=365627]Naked hot cams wom[/url][url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=328]Naked amateur webca[/url] de138d2

Pin Up Azerbaycan ?Onlayn Kazino: Pin Up Azerbaycan ?Onlayn Kazino – pin-up kazino

Letizia Fulkers naked before webcam – Live Porn Chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=329]Nude hot webcams mo[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=58]Naked hot cams wom[/url] 9d33efb

https://autolux-azerbaijan.com/# pin-up360

says:Just check this out, Watch nudeElla on the cam – Live Sex Chat for free!

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Naked hot webcams girls online porn show[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=59]Naked hot cams gir[/url] 245ad9d

Just check out the best Streamqueen21 fully naked on sexcam – online sex chat ever!

[url=http://shinyoungwood.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=777605]Naked hot cams wom[/url][url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=331]Nude amateur cams[/url] 7c0_107

buy nootropil 800mg – cost secnidazole 20mg generic sinemet

MayaJenkins nude stripping on cam for live sex video show absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Naked amateur cams model online porn show[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=61]Naked amateur webca[/url] 72fe7c1

pin up yukle: pin-up oyunu – pin up casino az

says:Just check this out, Watch nudeSarah before webcam – Online Porn Show for free!

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=62]Naked amateur webca[/url][url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=267]Nude amateur cams[/url] d9d33ef

sophia_leurre nude strip on cam for online porn movie webcam chat videos absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=367508]Nude hot webcams mo[/url][url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude amateur cams girls online sex show[/url] fb9793c

says:Just check this out, Blog for free!

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=271]Nude hot cams woma[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=367745]Nude hot cams girl[/url] 03772fe

pin-up casino giris https://azerbaijancuisine.com/# pin up apk yukle

pin-up 141

Discover the best latindolly Naked On Live Cam Girls Room ever for free!

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=273]Nude amateur cams[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=11823]Naked hot webcams g[/url] c2_b05a

Nice articl! Just check FREYAYGRETTA nude strip on cam for live sex video chat this out!

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Nude hot cams girls live sex show[/url][url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=274]Naked amateur webca[/url] 138d245

Watch nudeStella Live webcam – Sex Chat

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Naked hot webcams model live sex char[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=66]Naked hot webcams m[/url] d245ad9

Just check out the best rei1926 naked stripping on cam for online porn movie webcam chat ever!

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-hot-cams-girls-online-porn-show/]Nude hot cams girls online porn show[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=369420]Nude hot cams woma[/url] 9d33efb

Homepage von Naomie-sky nude on cwebam – live sex webcam chat

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=70]Naked amateur webca[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=370157]Naked hot webcams w[/url] ad9d33e

anal threesome Blog

[url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=761215]Naked hot webcams w[/url][url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=351]Nude amateur webcam[/url] 3c03772

Reesha_99 nude strip on cam for live sex chat

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=72]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-amateur-cams-girls-online-porn-char/]Naked amateur cams girls online porn char[/url] 38d245a

Nice article, thanks! Just check 𝒱 , 𝐼 𝒞 𝒯 𝒪 𝑅 𝐼 𝒜 nude before webcam – Live Sex Chaturbate this out.

[url=http://shinyoungwood.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=780247]Nude amateur cams[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=11880]Nude amateur cams[/url] fe7c4_b

Letizia Fulkers nude sexy before webcam Sex Chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude amateur cams model online sex show[/url][url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=761933]Naked amateur cams[/url] 9793c03

hydrea for sale online – buy generic ethionamide over the counter robaxin online

Discover the best Letizia Fulkers nude before adult cam – Live Sex Chat ever for free!

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-amateur-webcams-woman-online-porn-show-2/]Naked amateur webcams woman online porn show[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=11899]Nude hot webcams wo[/url] 38d245a

If you would like to obtain a good deal from this piece of writing then you have to apply such methods to your won website.

Just check out the best Your M nude before webcam – Live Sex Chat ever!

[url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=762300]Naked hot webcams w[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=11903]Naked amateur cams[/url] 7c7_4c7

mexico drug stores pharmacies: medicine in mexico pharmacies – reputable mexican pharmacies online

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexico drug stores pharmacies: Mexico pharmacy that ship to usa – mexican mail order pharmacies

https://northern-doctors.org/# medication from mexico pharmacy

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexican pharmacy – purple pharmacy mexico price list

http://northern-doctors.org/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican pharmacy – purple pharmacy mexico price list

http://northern-doctors.org/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies [url=http://northern-doctors.org/#]mexican mail order pharmacies[/url] reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexican northern doctors – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexican pharmacy

piracetam online – brand secnidazole sinemet 10mg canada

mexican pharmaceuticals online: Mexico pharmacy that ship to usa – mexican drugstore online

hydrea sale – hydrea price robaxin 500mg pill

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican pharmaceuticals online – buying prescription drugs in mexico

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexican mail order pharmacies

mexico pharmacy: Mexico pharmacy that ship to usa – mexico drug stores pharmacies

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexican northern doctors – buying prescription drugs in mexico

buying prescription drugs in mexico online [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]mexican pharmacy[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies

Mina_Khalifa nude strip on cam for live sex video chat

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=79]Nude amateur cams[/url][url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=374]Nude hot webcams mo[/url] 33efb97

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: Mexico pharmacy that ship to usa – medication from mexico pharmacy

http://northern-doctors.org/# medicine in mexico pharmacies

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: mexican pharmacy online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexican northern doctors – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

https://northern-doctors.org/# medication from mexico pharmacy

Find out Jasmina0001 naked strip on cam for live sex video chat for free 🙂

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-amateur-cams-girls-online-porn-show/]Naked amateur cams girls online porn show[/url][url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude hot cams girls live porn show[/url] 9793c03

to your liking, and quickly move to the section with Danielle Sky nude on webcam – live porn chat on this topic. All categories are packed enough to make

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=81]Nude amateur webcam[/url][url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=768721]Nude hot cams girl[/url] 3efb979

buying prescription drugs in mexico online [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]northern doctors[/url] buying prescription drugs in mexico

Discover the best sophia_leurre nude strip on cam for live sex movie webcam chat ever for free!

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Naked amateur webcams model online porn show[/url][url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=377]Nude amateur cams[/url] 45ad9d3

Excellent and high-quality Blog absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12069]Naked hot webcams w[/url][url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Naked amateur cams woman online porn char[/url] fe7c8_4

buying from online mexican pharmacy: mexican pharmacy online – mexican drugstore online

http://northern-doctors.org/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

medication from mexico pharmacy: northern doctors – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

SailormoonPlips naked stripping on cam for online sex movie webcam chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=380298]Naked hot cams gir[/url][url=http://hantechfa.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=16584]Naked amateur webca[/url] fb9793c

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexican drugstore online

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexican northern doctors – mexican mail order pharmacies

Your M nude before webcam – Live Sex Show videos absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=380657]Naked hot cams wom[/url][url=http://ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12090]Naked hot webcams g[/url] 33efb97

Discover the best Letizia Fulkers fully nude strip before cam for online porn webcam chat ever for free!

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=87]Nude hot cams mode[/url][url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=383]Naked hot webcams g[/url] 72fe7c7

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: buying from online mexican pharmacy – medication from mexico pharmacy

http://northern-doctors.org/# mexican pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=https://northern-doctors.org/#]buying from online mexican pharmacy[/url] buying prescription drugs in mexico

Nice article, thanks! Just check Nelly fully naked strip before cam for live porn chat this out.

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=381150]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=http://www.globaldream.or.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=sub08_02&wr_id=610]Nude amateur webcam[/url] 45ad9d3

reputable mexican pharmacies online: northern doctors pharmacy – mexican mail order pharmacies

https://northern-doctors.org/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

Excellent and high-quality Alexis Wylde fully nude webcam – live porn show absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=89]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=381371]Naked hot cams mod[/url] 72fe7c4

buying prescription drugs in mexico: mexican pharmacy online – medicine in mexico pharmacies

purple pharmacy mexico price list: mexican northern doctors – mexico pharmacy

http://northern-doctors.org/# medication from mexico pharmacy

Blog videos absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://hantechfa.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=16660]Nude hot webcams gi[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=381799]Naked amateur cams[/url] 2_9999f

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: mexican pharmacy – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

Excellent and high-quality Mia seleste Nude Live Hot Sex Cam absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Naked hot webcams girls live sex char[/url][url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=350]Nude amateur cams[/url] d245ad9

mexico pharmacy: Mexico pharmacy that ship to usa – mexican pharmaceuticals online

https://northern-doctors.org/# medication from mexico pharmacy

Nice article, thanks! Just check alessandraossa naked on Live Adult Webcams Girls this out.

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-amateur-cams-girls-live-sex-char/]Nude amateur cams girls live sex char[/url][url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Nude amateur cams model live porn char[/url] 3772fe7

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=http://northern-doctors.org/#]mexican pharmacy northern doctors[/url] mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican northern doctors – mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://northern-doctors.org/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://northern-doctors.org/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

Nice article, thanks! Just check JasmineXo fully naked stripping on cam for live porn video chat this out.

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=93]Nude amateur cams[/url][url=http://shinyoungwood.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=784726]Nude amateur webcam[/url] 33efb97

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexican drugstore online – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

Excellent and high-quality Elizabeth Adams , рџ€ naked on sex cam for live porn chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Nude amateur webcams girls live porn show[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12128]Naked hot cams mod[/url] 2fe7c5_

https://northern-doctors.org/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexico pharmacy: northern doctors – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

1 on 1 live sex chat videos absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=366]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12129]Naked hot cams wom[/url] 9d33efb

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: Mexico pharmacy that ship to usa – mexican mail order pharmacies

Excellent and high-quality web cam sex absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://shinyoungwood.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=785314]Nude hot cams woma[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12140]Naked amateur webca[/url] 3772fe7

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs [url=http://northern-doctors.org/#]mexican northern doctors[/url] buying from online mexican pharmacy

Discover the best cam for sex ever for free!

[url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=391]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=http://hantechfa.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=16801]Naked amateur cams[/url] 245ad9d

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexican pharmacy – mexican pharmaceuticals online

https://northern-doctors.org/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexican northern doctors – mexican mail order pharmacies

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexican mail order pharmacies

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexican pharmacy northern doctors – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

oral divalproex 250mg – order topamax 100mg generic topamax over the counter

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – buying prescription drugs in mexico

https://northern-doctors.org/# buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: cmq pharma – mexican drugstore online

mexican mail order pharmacies

https://cmqpharma.online/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

buying from online mexican pharmacy

best online pharmacies in mexico [url=https://cmqpharma.com/#]mexico pharmacy[/url] mexican drugstore online

mexico pharmacy [url=https://cmqpharma.online/#]cmq pharma[/url] buying prescription drugs in mexico online

buying from online mexican pharmacy [url=http://cmqpharma.com/#]online mexican pharmacy[/url] mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs [url=http://cmqpharma.com/#]mexico pharmacy[/url] mexican drugstore online

Discover the best sex video chat live ever for free!

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Naked hot cams model online porn show[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=98]Naked amateur cams[/url] 3c03772

says:Just check this out, for free!

[url=http://hantechfa.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=16976]Nude hot webcams wo[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=99]Nude amateur cams[/url] de138d2

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs [url=https://cmqpharma.com/#]mexico pharmacy[/url] mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

to your liking, and quickly move to the section with free sex live chat on this topic. All categories are packed enough to make

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=402]Nude hot cams woma[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12216]Naked hot cams gir[/url] 772fe7c

Nice article, thanks! Just check sex live cam this out.

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=405]Nude amateur cams[/url][url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=777234]Nude amateur cams[/url] 772fe7c

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies [url=https://cmqpharma.online/#]mexico pharmacy[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies

random sex cam videos absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=777561]Nude hot cams woma[/url][url=http://hantechfa.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=17028]Naked hot cams gir[/url] 33efb97

says:Just check this out, https://ftvgirlsfans.pro for free!

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Naked hot cams girls online sex char[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=388514]Nude amateur cams[/url] 3c03772

cheap norpace pills – buy pregabalin pills purchase chlorpromazine pills

buying from online mexican pharmacy [url=https://cmqpharma.online/#]mexican online pharmacy[/url] mexico pharmacy

Discover the best girlsbutts.org ever for free!

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=412]Nude amateur cams[/url][url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=406]Naked amateur webca[/url] 9793c03

reputable mexican pharmacies online [url=http://cmqpharma.com/#]mexican drugstore online[/url] п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

says:Just check this out, live sex chats free for free!

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=388957]Naked amateur webca[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-cams-woman-live-porn-char-2/]Naked hot cams woman live porn char[/url] 7c7_f11

Just check this out, free cam to cam sex chat

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=415]Naked amateur webca[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=389141]Naked amateur webca[/url] 4_153da

Discover the best live sex chat online ever for free!

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=389300]Naked amateur webca[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-webcams-girls-online-sex-char/]Naked hot webcams girls online sex char[/url] e7c8_6c

Excellent and high-quality live gay sex chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-hot-webcams-girls-online-sex-show/]Nude hot webcams girls online sex show[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=389479]Naked amateur webca[/url] 3efb979

Excellent and high-quality pornstar sex cam absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=111]Naked hot cams mod[/url][url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Naked hot webcams model live porn char[/url] 93c0377

cheap disopyramide phosphate without prescription – lamivudine for sale online generic chlorpromazine 100mg

Discover the best https://istrippers.pro ever for free!

[url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=779863]Naked hot webcams g[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=389975]Naked amateur webca[/url] 72fe7c7

Just check out the best sex chat is live ever!

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-amateur-webcams-woman-live-sex-show/]Naked amateur webcams woman live sex show[/url][url=http://hantechfa.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=17120]Nude amateur webcam[/url] b9793c0

order divalproex 250mg without prescription – where to buy aggrenox without a prescription order topiramate 100mg pills

Just check out the best live sex chat for free ever!

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=115]Naked hot cams gir[/url][url=http://hantechfa.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=17160]Nude amateur webcam[/url] e138d24

Excellent and high-quality live sex chat rooms absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12277]Naked hot cams wom[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=390554]Nude hot webcams wo[/url] 8d245ad

cam for sex absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=390885]Nude hot cams girl[/url][url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=781073]Nude hot cams girl[/url] 3efb979

Just check this out, live sex chat

[url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=422]Nude hot cams woma[/url][url=http://hantechfa.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=17221]Nude hot cams mode[/url] 03772fe

Excellent and high-quality couple sex cam absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=424]Naked amateur webca[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-amateur-webcams-girls-live-sex-char/]Naked amateur webcams girls live sex char[/url] fb9793c

Just check this out, #1 cam sex

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude hot cams girls live porn char[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12300]Nude amateur cams[/url] 3c03772

one on one sex cams

[url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=782513]Nude amateur webcam[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=121]Nude hot cams woma[/url] 8d245ad

Excellent and high-quality pornorgasm.pro absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Nude amateur webcams model online sex char[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=122]Naked hot cams wom[/url] 9793c03

Homepage von https://prettyass.org

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-amateur-cams-girls-online-porn-show-2/]Naked amateur cams girls online porn show[/url][url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=470]Nude hot webcams gi[/url] 45ad9d3

Just check this out, live indian sex chat

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Naked amateur webcams woman online sex show[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=124]Nude amateur cams[/url] d245ad9

anal threesome free cam sex scene

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-amateur-webcams-girls-live-porn-char/]Naked amateur webcams girls live porn char[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=125]Naked amateur webca[/url] 33efb97

adult sex cam absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=392754]Naked hot webcams g[/url][url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Naked amateur webcams model live sex show[/url] fe7c2_f

Excellent and high-quality https://sexydesktopgirls.pro absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=392853]Naked amateur webca[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12348]Naked hot webcams w[/url] ad9d33e

Just check out the best sex cam chat ever!

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-amateur-webcams-girls-online-porn-show/]Nude amateur webcams girls online porn show[/url][url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=482]Naked hot webcams m[/url] e138d24

to your liking, and quickly move to the section with #1 cam sex on this topic. All categories are packed enough to make

[url=http://hantechfa.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=17427]Naked hot cams mod[/url][url=http://ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12371]Naked hot cams gir[/url] 138d245

Just check this out, chat sex live

[url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=444]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Nude hot webcams woman live porn show[/url] 72fe7c3

Homepage von sexo live chat

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=491]Naked hot cams mod[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-hot-cams-model-online-porn-char-2/]Nude hot cams model online porn char[/url] e7c8_56

Nice articl! Just check free live sex cam chat this out!

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Naked amateur cams model online porn show[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=393686]Naked hot cams mod[/url] de138d2

Nice articl! Just check video chat live sex this out!

[url=http://shinyoungwood.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=793848]Nude hot cams girl[/url][url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Naked hot webcams girls live sex show[/url] d245ad9

order spironolactone 100mg without prescription – buy generic carbamazepine for sale purchase naltrexone online

purchase cyclophosphamide sale – purchase meclizine generic buy generic trimetazidine online

anal threesome wetpussypics.pro

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=498]Nude hot cams mode[/url][url=http://shinyoungwood.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=794074]Naked hot webcams w[/url] fb9793c

http://cmqpharma.com/# buying prescription drugs in mexico online

mexican mail order pharmacies

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs [url=https://cmqpharma.online/#]mexican online pharmacy[/url] mexican rx online

Discover the best free live sex chat rooms ever for free!

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-webcams-woman-live-porn-char/]Naked hot webcams woman live porn char[/url][url=https://naeunhome.cafe24.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=review&wr_id=448]Naked amateur webca[/url] 7c1_e99

Nice articl! Just check live sex chat this out!

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=510]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-amateur-cams-model-live-sex-char-3/]Naked amateur cams model live sex char[/url] 1_b6365

Find out free sex live chat for free 🙂

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-hot-cams-model-live-sex-show-2/]Nude hot cams model live sex show[/url][url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Naked amateur cams woman live porn show[/url] b9793c0

Just check this out, live chat sex chat

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-hot-cams-woman-live-sex-char/]Nude hot cams woman live sex char[/url][url=http://www.globaldream.or.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=sub08_02&wr_id=705]Nude amateur cams[/url] 9d33efb

Discover the best https://amateur-teen-nude.net ever for free!

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Naked hot webcams model online sex show[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-hot-cams-woman-online-porn-char-2/]Nude hot cams woman online porn char[/url] d245ad9

Excellent and high-quality free live webcam sex chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Nude amateur webcams model live sex show[/url][url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude hot webcams girls online sex show[/url] ad9d33e

cyclophosphamide tablet – purchase vastarel pills order vastarel without prescription

Discover the best http://www.bumfetish.com ever for free!

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-amateur-webcams-girls-online-porn-char-2/]Naked amateur webcams girls online porn char[/url][url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=787761]Nude amateur cams[/url] 5ad9d33

Find out live sex video chat for free 🙂

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=395764]Naked hot webcams w[/url][url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=788068]Naked amateur cams[/url] d33efb9

Nice articl! Just check communitysexy.net this out!

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=521]Nude hot webcams wo[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-webcams-woman-online-porn-char-2/]Naked hot webcams woman online porn char[/url] 8d245ad

Nice article, thanks! Just check https://crazyamateurporn.com this out.

[url=http://shinyoungwood.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=795579]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=524]Nude hot cams girl[/url] 3c03772

sex live chat free

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Nude amateur webcams model live sex show[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-webcams-model-live-porn-show/]Naked hot webcams model live porn show[/url] 5ad9d33

Just check out the best 1 on 1 sex cams ever!

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-hot-cams-woman-online-sex-char-2/]Nude hot cams woman online sex char[/url][url=http://ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12490]Nude hot cams mode[/url] 3efb979

Nice articl! Just check fastsexxx.com this out!

[url=http://shinyoungwood.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=796215]Nude amateur cams[/url][url=http://www.globaldream.or.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=sub08_02&wr_id=715]Naked amateur cams[/url] 45ad9d3

Find out sex cams free for free 🙂

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-amateur-webcams-girls-online-sex-char-2/]Naked amateur webcams girls online sex char[/url][url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=790029]Naked hot cams mod[/url] 9d33efb

Discover the best live adult sex chat ever for free!

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=397049]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-webcams-model-live-porn-char-2/]Naked hot webcams model live porn char[/url] 7c0_f63

Find out teen sex cams for free 🙂

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-webcams-girls-live-sex-show/]Naked hot webcams girls live sex show[/url][url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude hot webcams model online sex show[/url] c7_ea25

says:Just check this out, indian live sex chat for free!

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=149]Nude hot webcams mo[/url][url=http://shinyoungwood.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=797125]Naked amateur webca[/url] 5ad9d33

to your liking, and quickly move to the section with hot-sexyxx.com on this topic. All categories are packed enough to make

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-amateur-webcams-model-online-porn-show/]Nude amateur webcams model online porn show[/url][url=http://shinyoungwood.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=797397]Nude hot cams girl[/url] 3c03772

Excellent and high-quality cam sex free absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-amateur-webcams-woman-live-porn-show/]Nude amateur webcams woman live porn show[/url][url=http://shinyoungwood.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=797539]Naked hot cams wom[/url] fb9793c

Excellent and high-quality chate live sex absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://hantechfa.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=18070]Nude amateur webcam[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-cams-woman-live-porn-char-3/]Naked hot cams woman live porn char[/url] 33efb97

Discover the best free live sex cams ever for free!

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=398208]Nude amateur webcam[/url][url=http://shinyoungwood.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=798073]Naked amateur cams[/url] 72fe7c4

anal threesome gay sex live cam

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=398457]Naked hot cams wom[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-hot-cams-woman-online-porn-show/]Nude hot cams woman online porn show[/url] c1_2a77

aldactone 100mg usa – dilantin uk buy naltrexone 50mg online

Find out sex toys live cam chat for free 🙂

[url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12542]Nude hot cams girl[/url][url=http://hantechfa.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=18180]Nude hot webcams gi[/url] fe7c4_3

Discover the best live sex video chat ever for free!

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-hot-webcams-woman-live-porn-show-2/]Nude hot webcams woman live porn show[/url][url=http://lashnbrow.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=2393043]Naked amateur webca[/url] 9793c03

Just check out the best #1 cam sex ever!

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Nude amateur cams woman live sex char[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=399337]Nude amateur webcam[/url] de138d2

Excellent and high-quality sex cam chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=793156]Nude hot webcams mo[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=158]Nude hot webcams gi[/url] 3772fe7

Find out indian sex cams for free 🙂

[url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Nude amateur webcams girls online sex show[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=159]Nude amateur cams[/url] ad9d33e

pokethathole.com absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=550]Nude hot webcams mo[/url][url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=793708]Nude amateur cams[/url] 33efb97

free sex live chat videos absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=552]Naked hot webcams m[/url][url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Naked hot webcams girls live sex show[/url] 8d245ad

Discover the best free sex web cam ever for free!

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-amateur-cams-girls-online-sex-show-2/]Naked amateur cams girls online sex show[/url][url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=794846]Naked hot webcams w[/url] de138d2

Find out indian live sex chat for free 🙂

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=163]Nude hot webcams wo[/url][url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=795094]Naked hot webcams w[/url] 3772fe7

anal threesome online sex cam

[url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12595]Naked hot cams mod[/url][url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=164]Nude amateur webcam[/url] de138d2

Nice article, thanks! Just check cam live sex this out.

[url=http://www.globaldream.or.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=sub08_02&wr_id=750]Naked amateur cams[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-amateur-webcams-woman-online-porn-char-2/]Nude amateur webcams woman online porn char[/url] fb9793c

says:Just check this out, sex cams live for free!

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=166]Nude hot webcams gi[/url][url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12627]Naked amateur cams[/url] 138d245

Homepage von chat live sex

[url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12637]Nude amateur webcam[/url][url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=567]Naked hot webcams g[/url] 2fe7c5_

Excellent and high-quality one on one live sex chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/nude-amateur-cams-woman-online-porn-char/]Nude amateur cams woman online porn char[/url][url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=796128]Nude amateur cams[/url] 72fe7c7

Just check this out, asian sex cams

[url=http://remote.ecostm.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=c1&wr_id=12651]Naked hot webcams w[/url][url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=401937]Nude amateur webcam[/url] d33efb9

to your liking, and quickly move to the section with #1 cam sex on this topic. All categories are packed enough to make

[url=http://test.aocoolers.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=pension&wr_id=170]Naked hot cams wom[/url][url=http://www.globaldream.or.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=sub08_02&wr_id=759]Nude hot cams woma[/url] 3772fe7

online live sex chat

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=402109]Naked hot cams gir[/url][url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude hot webcams girls online sex show[/url] c03772f

Excellent and high-quality roseyyxox nude before webcam – Live Sex Chat absolutely free and easy to watch on any device, just

[url=https://sample115.tlogsir.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=tl_product02&wr_id=576]Naked hot cams mod[/url][url=http://shinyoungwood.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=801940]Nude hot cams woma[/url] 245ad9d

anal threesome cam for sex

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=402206]Naked amateur webca[/url][url=http://hantechfa.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=18559]Naked hot webcams m[/url] fe7c5_c

Stella live chat nude before webcam – Live Chaturbate

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude amateur cams girls online porn show[/url][url=https://community.katawatbusiness.com/question/naked-hot-cams-woman-live-porn-show-2/]Naked hot cams woman live porn show[/url] fe7c7_7

Just check this out, Cheddarbarbie naked on sex cam for live porn chat

[url=https://trust-used.com/best-gaming-laptop-models/]Nude amateur cams girls online porn char[/url][url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=798048]Nude hot webcams gi[/url] b9793c0

says:Just check this out, sessotube.pro for free!

[url=http://www.kiccoltd.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=798272]Nude amateur cams[/url][url=http://hantechfa.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=18608]Naked hot cams wom[/url] 3efb979

says:Just check this out, ebony live sex chat for free!

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=402546]Naked hot cams wom[/url][url=http://www.globaldream.or.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=sub08_02&wr_id=780]Naked amateur webca[/url] c03772f

Nice articl! Just check free webcam live sex chat sites this out!

[url=http://thinktoy.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=customer2&wr_id=402618]Nude amateur webcam[/url][url=https://toteblogs.com/posts/Best-Vitamin-C-Serums-for-Brighter-Skin-]Naked hot webcams model live sex show[/url] ad9d33e

buy flexeril without prescription – buy olanzapine pills vasotec 5mg sale

ondansetron pill – buy generic oxybutynin buy requip 1mg

cyclobenzaprine ca – flexeril 15mg cheap buy enalapril 10mg online

order ondansetron online – ondansetron order online ropinirole 1mg ca

buy ascorbic acid no prescription – buy kaletra prochlorperazine medication

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexico pharmacy – reputable mexican pharmacies online

reputable mexican pharmacies online

http://cmqpharma.com/# reputable mexican pharmacies online

buying prescription drugs in mexico

buy durex gel for sale – zovirax us cheap latanoprost

order ascorbic acid without prescription – purchase ferrous sulfate compro sale

purchase durex gel for sale – order durex gel cheap order generic latanoprost

mexican drugstore online

https://cmqpharma.online/# mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

best online pharmacies in mexico

mexican rx online: buying from online mexican pharmacy – purple pharmacy mexico price list

buy rogaine generic – proscar price propecia 5mg pill

I like this blog it’s a master piece! Glad I noticed this ohttps://69v.topn google.Blog monry

order leflunomide 10mg sale – risedronate 35mg uk cartidin pills

arava over the counter – alfacalcidol order cartidin pills

purchase minoxidil without prescription – rogaine for sale online finasteride 1mg uk

calan 240mg cheap – buy diovan online purchase tenoretic for sale

atenolol 50mg price – purchase coreg sale order carvedilol 25mg without prescription

atenolol 100mg us – cost tenormin 100mg coreg for sale online

buy verapamil generic – valsartan sale buy tenoretic paypal

atorvastatin buy online – order nebivolol 5mg for sale purchase nebivolol pill

atorvastatin pills – order atorvastatin order generic nebivolol 20mg

buy gasex generic – diabecon usa cheap diabecon tablets

https://indiapharmast.com/# world pharmacy india

cross border pharmacy canada: canadian pharmacy no scripts – canadapharmacyonline legit

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: buying from online mexican pharmacy – reputable mexican pharmacies online

top online pharmacy india [url=http://indiapharmast.com/#]world pharmacy india[/url] top 10 online pharmacy in india

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican drugstore online – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

best online pharmacies in mexico: mexico pharmacy – medicine in mexico pharmacies

http://foruspharma.com/# reputable mexican pharmacies online

indian pharmacy [url=https://indiapharmast.com/#]Online medicine home delivery[/url] buy medicines online in india

canada pharmacy: cheap canadian pharmacy online – canadian pharmacy checker

lasuna price – order diarex online cheap himcolin order online